The Major Project is a year-long, research-driven creative endeavor that marks the culmination of the MA Digital Arts program. It involves developing a substantial body of work that integrates theoretical and practical methodologies, supported by critical analysis and documentation. Through presentations, reviews, and independent research, students refine their concepts and demonstrate advanced project management, leading to a final public exhibition that showcases their ability to execute and present a professional-standard artistic research project.

Introduction

When I began this project, I was drawn to the idea of many possible futures existing side by side. I wanted to explore how art can hold both hope and fear, utopia and dystopia, and how memory and technology constantly shape these visions. The vinyl record became my symbol of the past: physical, warm, and enduring, holding sound in grooves that resist time. The UV laser became my symbol of the future: precise, fleeting, and immaterial, leaving only temporary traces. Bringing the two together gave me a way to stage a dialogue between nostalgia and possibility, loss and invention.

This theme is connected to the way we live today, suspended between promises of progress and the persistence of ghosts from the past. Thinkers like Jacques Derrida (1994) and Mark Fisher (2014) describe this as hauntology and the “slow cancellation of the future”. Concepts that helped me see my project as a reflection on culture. By staging different futures, my aim is to create a space of reflection. In this sense, my work aligns with the approach of speculative design (Dunne & Raby, 2013), treating imagined futures as tools for questioning rather than answers. For me, this project is about making uncertainty visible, and inviting others to feel how fragile and powerful the idea of the future really is.First Crit

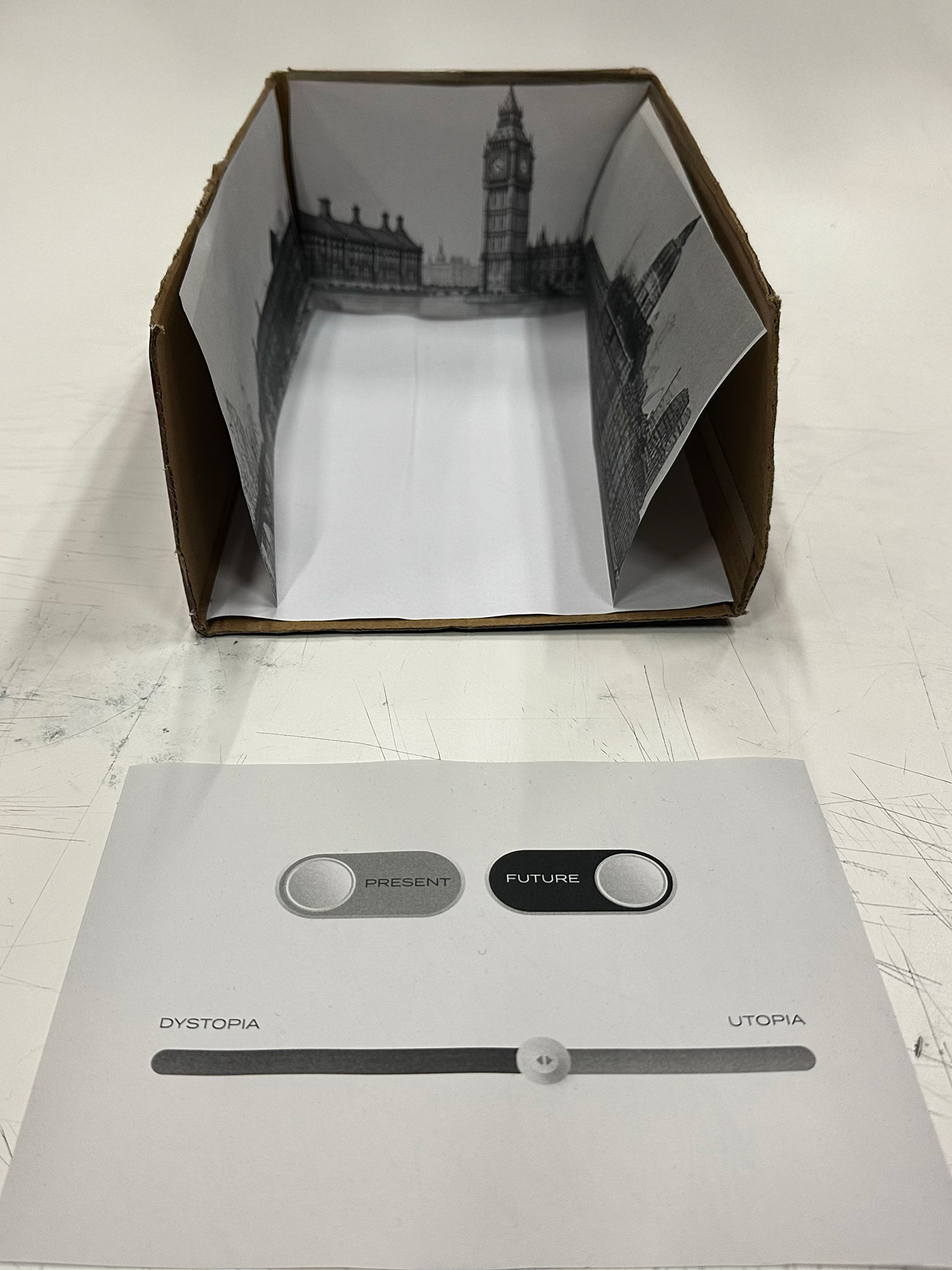

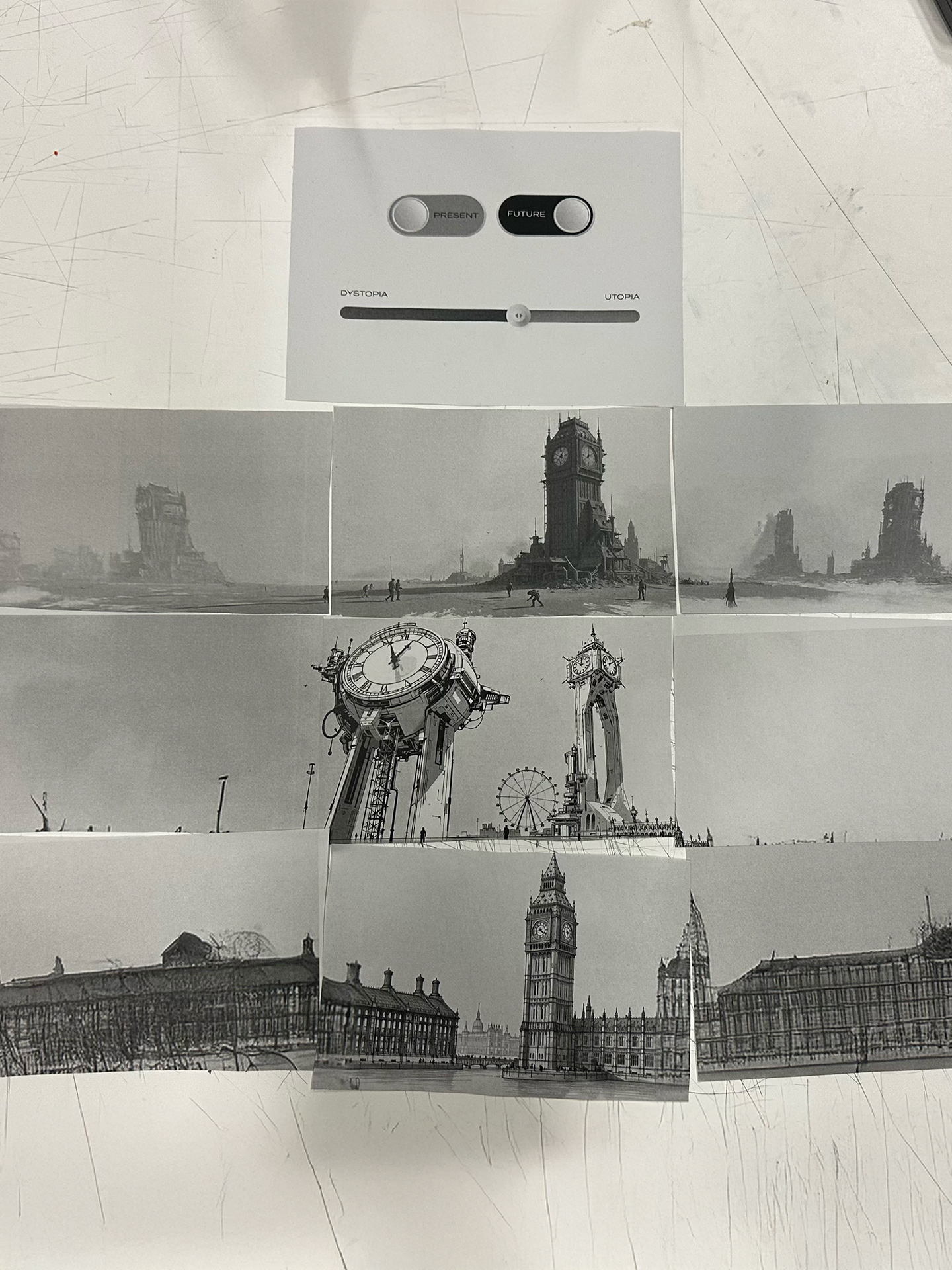

For my first crit, I started shaping the project as a futuristic city that existed between utopia and dystopia. At this stage it was all very hands-on: I sketched and built paper mock-ups to imagine what the city might look like. I wanted to capture the tension between a clean, idealised, technologically advanced environment and one that was collapsing into decay. The act of working with paper helped me think about form and fragility at the same time — it felt important that the city could be both beautiful and unstable, full of promise but also on the edge of decline.

My inspirations came from science fiction, speculative architecture, and the way real cities constantly shift through cycles of growth and deterioration. Through these references I built a visual language of high towers, glowing grids, and shadows of ruin. I also imagined a way for the audience to choose between futures, a slider that would move the city between utopian light and dystopian collapse, letting viewers decide which version they wanted to see. Presenting this first version made me realise that the project wasn’t only about creating a cityscape, it was about letting people feel the fragile balance between utopian desire and dystopian fear, and giving them a role in shifting that balance themselves.

Research

My research for this stage focused on how the city has been imagined as both utopia and dystopia in culture and theory. Science fiction has long used urban space to reflect collective hopes and anxieties, from the ordered skylines of Metropolis (1927) to the fractured landscapes of Blade Runner (1982). Henri Lefebvre’s The Production of Space (1991) reminded me that cities are not neutral but socially produced, carrying the weight of politics and power. Fredric Jameson (2005) also argues that utopian and dystopian visions act as mirrors of the present, exaggerating its contradictions. These ideas helped me see my imagined city not simply as a design exercise, but as a way of thinking critically about the balance between progress and decline.

Results and Reflection

The main question that emerged from this first crit was: what is our future? To answer it, I began thinking about utopia and dystopia as ways of imagining. A utopia is often understood as a perfected society, orderly, safe, and free from conflict, while dystopia exposes the cracks beneath that perfection, showing decay, inequality, or oppression. What struck me was how these two concepts are always entangled. Every utopian vision carries the shadow of dystopia, and every dystopia still contains traces of human hope. My city became a way to stage this entanglement, showing how progress and decline can exist side by side.

At the same time, the crit pushed me to think on a smaller and more realistic scale. Instead of imagining vast cityscapes, I started to notice how meaning is carried in details, a single building, a familiar landmark, or a space that never changes. For example, when I thought about Big Ben, I realised it has remained visually the same for generations. Its persistence makes it a symbol of continuity within change. This reflection helped me understand that the future might not only be about dramatic transformations but also about what endures. In this sense, my project began to shift from designing an abstract “future city” to asking how people experience change and permanence in the everyday.

Post-Digital

A key element I want to carry into my Major Project is the idea of the post-digital. This concept suggests that digital and physical realities can no longer be separated, they have merged into one continuous environment. Instead of treating technology as a surface that sits on top of the city, I want to see it as part of the city’s very fabric. In the context of my futuristic city, this raises questions about how digital networks shape urban evolution, how digital traces might remain as ruins, and what happens when the line between virtual and real space dissolves altogether. Thinkers such as Cramer (2015) describe the post-digital as a shift from novelty to integration, where digital technology is no longer “new” but something embedded, messy, and taken for granted. This perspective gives me a useful lens to rethink how cities might carry both physical and digital scars into the future.

A project that shaped this approach was The Internet After Us, where I imagined the ruins of the internet if humanity were gone, abandoned data, obsolete networks, and forgotten algorithms scattered like archaeological remains. That earlier work showed me how digital and physical decay can coexist, and how ruins themselves tell stories about the societies that built them. For my Major Project, I want to use this post-digital lens to show a city that is neither purely utopian nor dystopian, but layered with traces of data, AI, automation, and physical matter. The challenge will be to represent this mixture in a way that feels tangible, so that digital remnants appear as real and weighty as bricks or steel.

Pecha Kucha

Delivering my project as a Pecha Kucha was an important moment because it forced me to tell the story of Two Futures in a very sharp and structured way. With twenty slides and twenty seconds per slide, I had to focus on the essentials: defining what we mean by “future,” exploring the tension between utopia and dystopia, and showing how projection mapping could turn that into an interactive experience. I spoke about the city as a place that shifts depending on choices, moving between green, bright utopian visions and darker, overcrowded dystopian ones. What stood out was how the format highlighted the role of audience agency: instead of passively watching, they would shape the city’s direction, making the theme of choice central to the work.

The presentation also helped me test how my ideas connected with others. I drew on examples like Tim Maughan’s Infinite Detail to show how collapse can lead to both renewal and destruction, and I framed these ideas around environmental, social, and ethical questions. Could technology liberate us or control us? Who decides what counts as utopia or dystopia? These were questions I wanted to leave the audience with. Looking back, the Pecha Kucha was a performance that clarified the philosophical core of my project: every decision, big or small, contributes to the kind of future we end up living in.

Reflection

The feedback from my Pecha Kucha highlighted that I was beginning to engage with utopia and dystopia in a deeper way, but also that my focus on building an interactive environment was limiting how far I could take these ideas. I was encouraged to explore the two axes of present/future and utopia/dystopia through more varied design experiments, rather than only through interactivity. What struck me most was the suggestion to think about the sensory dimensions of these futures, their smells, sounds, and textures. and to consider making 3D artefacts that could embody them. This pushed me to expand my approach, seeing utopia and dystopia as lived, material, and multisensory experiences.

A Monument of Waste

This installation struck me as a powerful representation of dystopia. The mountain of discarded clothes piled high against the wall felt like a monument to excess, waste, and collapse. It spoke about the overwhelming presence of consumer culture, where materials meant to clothe and protect us instead accumulate as haunting remains. What made it dystopian was not only the physical heaviness of the pile but also the silence around it, a reminder of lives, labour, and stories erased in the process of mass production.

Second Crit

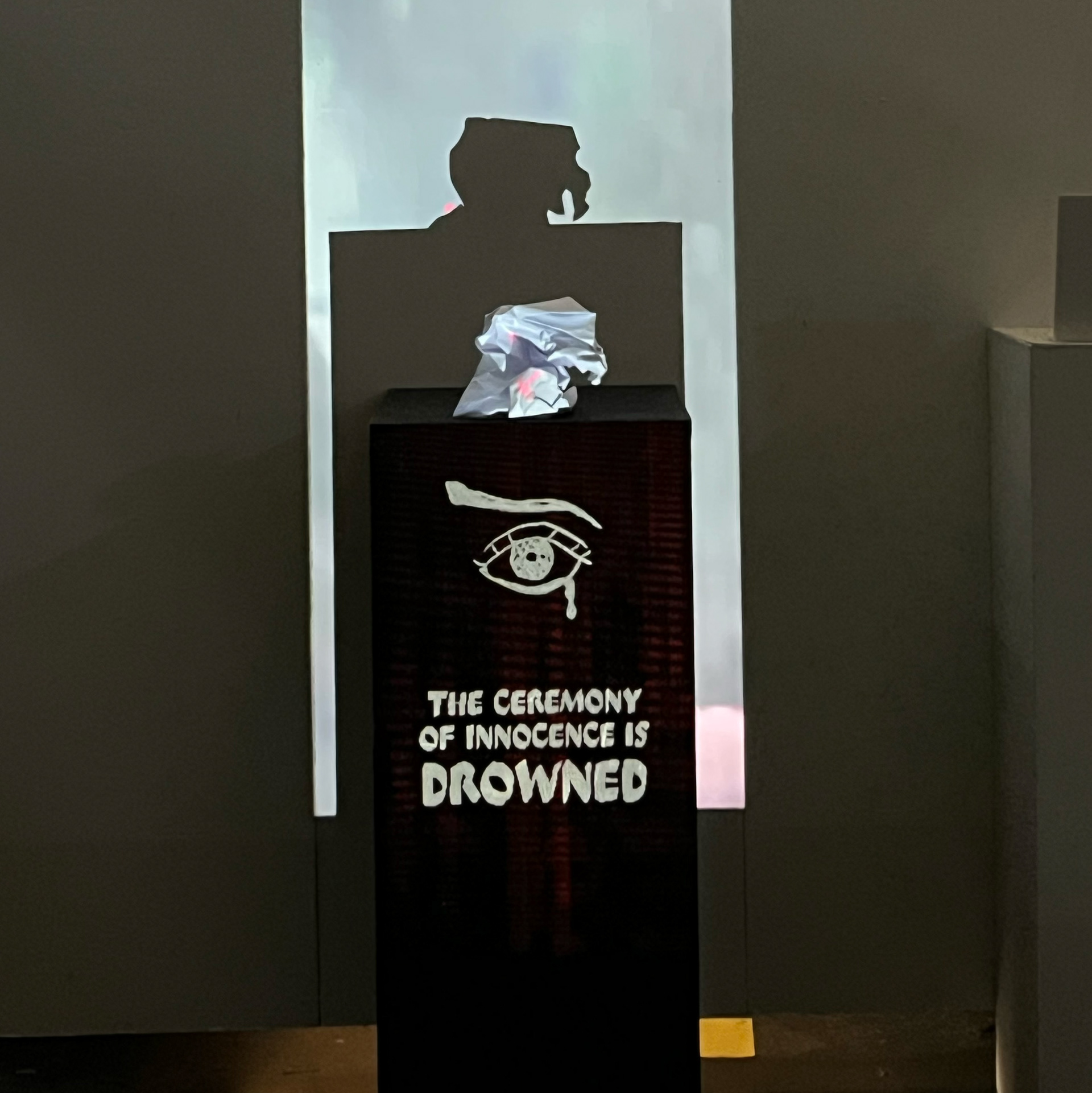

For the second crit, I developed two contrasting visions of the future, one dystopian and one utopian, framed through the role of technology. The dystopian future, titled The Ceremony of Innocence is Drowned, imagined a world where technology became a tool of control and restriction. The broken structure symbolised collapse and lost potential, animated with projections of crumbling cities and static echoes that suggested abandonment. The phrase, borrowed from W.B. Yeats’ The Second Coming (1920), gave this vision a poetic weight, capturing the sense of order dissolving into chaos. This version of the future reflected a path where inaction and unchecked systems led to decay, leaving behind only ruins and fragments.

In contrast, the utopian vision, To a Green Thought in a Green Shade, presented a world shaped by decentralisation, sustainability, and balance. Here, the structure became a symbol of harmony between technology and nature, brought to life with projections of futuristic cities full of possibility. The addition of ivy reinforced the idea of growth and renewal, while the phrase from Andrew Marvell’s The Garden (1681) grounded the work in a vision of peace and connection. Unlike the dystopian path, this future asked what might happen if technology was used responsibly, to empower communities and create spaces where life could thrive.

Research

In shaping these two contrasting futures, I drew inspiration from literature that explores the fragile line between utopia and dystopia. Tim Maughan’s novel Infinite Detail (2019) was especially important, as it imagines a world where the collapse of the internet creates both liberation and disaster. On one hand, communities free themselves from corporate surveillance and rediscover autonomy, while on the other, cities fall into chaos without the networks they depended on. This duality mirrored the futures I wanted to present: one where technology entrenches control and decay, and another where decentralisation opens space for sustainability and renewal. By combining these ideas with poetic references from W.B. Yeats’ The Second Coming and Andrew Marvell’s The Garden, I began to see how cultural texts could give language and depth to the visual contrasts in my project, grounding them in wider traditions of imagining what comes after collapse or harmony.

Results and Reflection

The feedback from this crit helped me see that while the contrast between utopia and dystopia was strong, the real value of the work lay in how these futures could be explored through material and sensory details. The poetic references gave the project a symbolic richness, but I was encouraged to push further in defining what these worlds actually feel like, their textures, sounds, and atmospheres. This made me realise that the project was not only about showing two futures, but also about making them tangible in ways people could sense and imagine themselves within. It also highlighted the importance of not getting too fixed on the binary, but instead exploring the grey areas where utopian and dystopian qualities overlap, much like in Infinite Detail where collapse and renewal exist side by side.

Third Crit

For the third crit, I continued working with the two futures I had developed earlier, one dystopian and one utopian, but this time I shifted from digital 3D models to a more physical installation. Instead of relying on 3D-printed objects, I experimented with folded and crumpled paper forms as the base structures. This decision was partly practical but also symbolic: paper, fragile and impermanent, gave the installations a raw and human quality that contrasted with the polished surfaces of digital models. The dystopian piece, The Ceremony of Innocence is Drowned, used rough paper shapes combined with glitch-like projections and static textures, evoking collapse and decay. The utopian piece, To a Green Thought in a Green Shade, incorporated smoother surfaces and overlays of green light, creating an atmosphere of growth, renewal, and balance.

This transition into physical materials made the work feel more grounded and opened up new possibilities for how projection could interact with real surfaces. The paper structures caught light in unexpected ways, producing shadows and distortions that added depth to the projected imagery. This showed me that materiality could play as big a role as digital imagery in communicating the feeling of each future. The installation became less about creating a polished “final city” and more about testing how fragile, temporary objects could carry large conceptual weight. It was also an important step in making the project more experiential, moving closer to something an audience could physically encounter rather than just imagine on a screen.

Research

Moving from digital 3D models to fragile paper structures opened up a new layer of meaning in the project, connecting it to ideas of materiality and impermanence. Paper, as Tim Ingold (2013) argues in Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture, is not just a passive medium but an active material that carries traces of process, fragility, and temporality. Its folds, creases, and vulnerabilities reflect the unstable nature of imagined futures, always in flux, always at risk of being reshaped. This perspective helped me see that using paper was not a compromise but a conceptual choice: it allowed the projections to interact with surfaces that were themselves unstable, mirroring the precarious balance between utopian and dystopian visions. By working with such a delicate material, the installation aligned with theories of ephemerality in art, where the temporary and the fragile become metaphors for cultural and technological futures (Phelan, 1993).

Interim Show

For the interim show, I proposed a work titled The Wall Remembers, set in the Undercroft of the Queen Anne Building. This quiet basement houses stone heads carved over 300 years ago for the Painted Hall, which were never used and have remained hidden from view. My idea was to bring these forgotten sculptures to life using projection and sound, turning them into silent storytellers. Each head would carry a different emotional tone, some evoking peace, healing, or community, others suggesting abandonment, war, or silence. Rather than creating a clear narrative, I wanted the installation to feel like walking through memory, where the past remembers us as much as we remember it. By using the space itself as material, I was not adding something new, but revealing what was already there.

The proposal was inspired partly by Rafael Lozano-Hemmer’s Pulse Room, which transforms individual heartbeats into a shared archive of light. I was struck by how it connects personal traces to collective memory, and I wanted to attempt something similar with these stone heads. In my installation, the projections and ambient sounds would act as fragments of memory, creating a living archive out of what had been silent for centuries. This stage of the project allowed me to step away from purely imagined cities and into a real historical space, merging utopian and dystopian tones with tangible heritage. It was a turning point that showed me how my project could balance speculative futures with forgotten pasts, and how projection mapping could serve as a bridge between the two.

Reflection

The interim show was the first time I installed the work in a real space, and it completely shifted my understanding of what the project could be. Working with the stone heads in the Undercroft taught me how different it feels to move from planning on paper or screen to physically setting up in a historical site. I had to think about scale, projection angles, sound placement, and how people would walk through the room, practical challenges that became just as important as the concept itself. What I learned was that the space and the work are inseparable: the architecture, textures, and atmosphere shaped the piece as much as my visuals did. This experience gave me confidence for the final installation, because it showed me that making the work real is not just about translating an idea but about responding to the site, adapting, and letting the place itself guide the outcome.

LEGOgraphy

One of the small but important experiments I carried out was projecting onto a LEGO figure, which I called Legography. This exercise was playful and a valuable study in precision. By working with the figure’s distinct edges, curves, and lines, I learned how projection mapping responds to different shapes, and how crucial alignment is when working on a 3D object. The simplicity of the LEGO form made mistakes very visible, which helped me refine my approach and understand how light can either enhance or distort a surface. This experiment gave me the confidence to later project onto more complex forms, teaching me to pay close attention to how visuals wrap around physical structures and how projection can transform even the smallest object into a site of storytelling.

Projection on Plants

At one point, I tried projecting onto plants, and the result stayed with me. The light didn’t land neatly the way it does on a wall, it scattered across leaves, slipped through gaps, and created unexpected shadows. It felt as if the plants were breathing with the projection.

BOARC Visit

The trip to BOARC was less about theory and more about experiencing how an art research centre actually works on a day-to-day level. It was an opportunity to see the space, meet people, and spend time in a relaxed environment while still learning through practice. What made it important for me was the chance to set up a small projection and test my work in front of others. Projecting in a public setting gave me a sense of what it feels like to share ideas beyond a private studio.

Major Proposal

My major project proposal, Re:Charge, brought together two technologies, the vinyl record and the UV laser, to explore how we imagine futures at the edge of utopia and dystopia. The vinyl represented memory and the analog past: circular, fragile, and resistant, a reminder of how culture survives when digital systems fail. The laser stood for the opposite, speed, progress, and light, a symbol of futuristic energy, medicine, and even science fiction. When these two elements meet on a spinning glow-in-the-dark record, they create glowing lines that flare and fade, a temporary conversation between what is remembered and what is possible. For me, this was about showing that both utopia and dystopia are fragile performances, always imagined, always erased, and always drawn again.

What made the proposal exciting was that it was about the process. Each test with different UV sprays, laser strengths, and turntable speeds became a performance in its own right, revealing how materials respond to light and time. The gallery installation plan extended this idea: filming the glowing record from above and projecting it at a larger scale, alongside a smaller screen showing the making process, so that the audience could experience both the artwork and the act of creating it.

Glow in the dark

The idea of using glow-in-the-dark materials came to me almost by accident, while I was experimenting with how light behaves on different surfaces. I realised that phosphorescent paint could hold light for a few seconds before it faded, creating a perfect metaphor for memory and time. That fading glow immediately connected to my project’s themes of utopia and dystopia, the idea that hope and collapse are never permanent but always temporary, always in flux. It felt poetic that the material itself carried this meaning, without me having to force it. The glow became both a medium and a message: a way of showing that the future is not fixed, but something that shines briefly, disappears, and must constantly be reimagined.

Reflection

Writing and presenting my major proposal was the point where the project finally became clear to me. Until then, I had been moving between ideas of cities, interactivity, and fragments of futures, but the act of putting everything into a structured proposal forced me to focus on what mattered most: the dialogue between past and future, memory and hope. The vinyl and laser gave me a simple but powerful language to explore that tension, and the glow-in-the-dark element tied it together in a way that felt both poetic and grounded. More importantly, the proposal showed me that the project didn’t need to provide answers, its strength was in raising questions and creating experiences where uncertainty could be felt. This reflection gave me confidence to move forward, knowing I had found a core idea that could carry me through the rest of the journey.

Summer Crit 01

For the first summer crit, I began testing the core idea of Re:Charge in practice: using a vinyl record coated with glow-in-the-dark spray paint and inscribing it with a UV laser. This was the first time the concept moved beyond planning and into real experimentation, and it immediately showed me the poetic quality of the material. As the record spun, the laser drew temporary glowing lines that burned brightly and then slowly faded. That fading glow felt like a perfect metaphor for fragile futures, moments of light that appear, disappear, and must be constantly redrawn. The test confirmed that the material itself could carry the meaning of the project, without the need for overcomplication.

This stage was about discovering how the physical process worked and what it could express. I learned how different coatings, speeds, and angles of the laser created different intensities and durations of glow, almost like different moods of memory and time. The crit helped me realise that this wasn’t just a technical experiment but a performance: each gesture with the laser was a drawing that would inevitably vanish, leaving behind only the trace of what had been. That balance between presence and disappearance became the starting point for how I would shape the installation going forward.

Research

The first experiments with glow-in-the-dark vinyl connected directly to ideas of ephemerality and performance in contemporary art. Peggy Phelan (1993) argues that performance is defined by its disappearance, its value lies in the fact that it cannot be fully captured or repeated, only experienced in the moment. This aligned with the way the glowing lines appeared and faded, leaving only memory behind. Similarly, Gaston Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space (1994) influenced how I thought about the vinyl as a space of imagination, where fleeting light transforms an ordinary surface into something dreamlike and charged with meaning. In the field of light art, scholars such as Christopher Salter (2010) have shown how technological media can produce immersive, time-based experiences that blur the boundary between material and immaterial. These perspectives helped me see my tests not just as technical trials, but as explorations of how light, time, and memory intertwine.

Results and Reflection

The first summer crit made it clear that while the glow-in-the-dark experiments were visually engaging, the project needed stronger grounding beyond the effect. Feedback pointed out the lack of connection with sound and the limitations of interactivity, as well as the need to define why I was making this work instead of simply creating another interactive installation. More importantly, it highlighted the absence of proper scholarly, art-historical, and cultural framing, which meant the piece risked floating without a clear intellectual anchor. The advice I received was practical and direct: to engage with political and social aesthetics, draw from thinkers like William Morris on utopia, and bring in references to specific artworks such as 50 Centric’s painting or other primary sources. It also encouraged me to deepen my research by using libraries instead of relying on surface-level online searches. This reflection pushed me to treat the project not just as an experiment with materials, but as a work that needed cultural weight and a clear position within art and theory.

Summer Crit 02

For the second summer crit, I moved from the spinning vinyl into a new object: a glow-in-the-dark brain. The installation showed the brain slowly rotating in the dark, becoming a stage for interaction with the audience. People were invited to point UV laser lights at it, and each time they did, the surface lit up in small glowing spots. The brain didn’t glow by itself; it only became visible where someone chose to shine the light. This simple mechanic created a strong visual metaphor, where the presence of others literally shaped what could be seen.

The piece opened up questions about how our inner worlds are revealed and influenced in contemporary life. Just as the glowing brain only appeared when touched by someone else’s laser, our thoughts and feelings today are often made visible through external forces: social media, data tracking, or even subtle acts of surveillance. The work asked how much of what we think or show is really our own, and how much is shaped by the gaze of others. In this way, the spinning brain became more than an object — it became a metaphor for visibility, consent, and control in a world where the line between private thought and public exposure grows increasingly thin.

Research

The glowing brain experiment connected closely with theories of surveillance and visibility. Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish (1977) introduces the idea of the panopticon, where individuals regulate their own behaviour because they know they might be watched, a concept that resonates with how the brain only lights up when an external beam is directed at it. More recently, Shoshana Zuboff (2019) has described surveillance capitalism, where our data, emotions, and choices are constantly extracted and shaped by unseen systems. These frameworks helped me interpret the work not simply as an interactive object but as a metaphor for how thought itself is made visible, commodified, and influenced by external forces. The fact that the brain only glows when someone else activates it highlights the fragility of autonomy in a world where visibility is rarely under our full control.

Results and Reflection

The main feedback from Summer Crit 2 was that the background video needed to be more relevant to the core concept, rather than just acting as a decorative layer. While the glowing brain worked well as a metaphor, the installation still lacked clarity in how it would operate in a gallery context. The question raised was: what does the video underneath actually add to the piece, and how does it connect to the themes of surveillance, influence, and visibility? This pushed me to rethink how the brain should interact with its environment. The crit made it clear that I needed to refine both the visual language and the conceptual framing so that the work didn’t rely only on the striking effect of the glowing brain, but instead communicated its ideas more cohesively. These issues directly shaped the direction I took in Crit 3, where I started addressing how to link the glowing brain with live digital feeds and how it might behave in a gallery space.

Hastings Trip

The Hastings trip gave me the time and space to step back from constant experiments and think carefully about what my final exhibition could look like. Away from the usual routine, I was able to focus on writing a clear plan that tied the glowing brain concept to larger questions about social media, influence, and attention. Being in a different environment helped me clarify the technical needs, from UV lighting on timers to projection mapping, and also pushed me to think about how the work would function in a real gallery space with an audience. Writing the final exhibition plan in Hastings felt like an important turning point, it transformed the project from scattered tests into a structured vision of what I wanted to build and present.

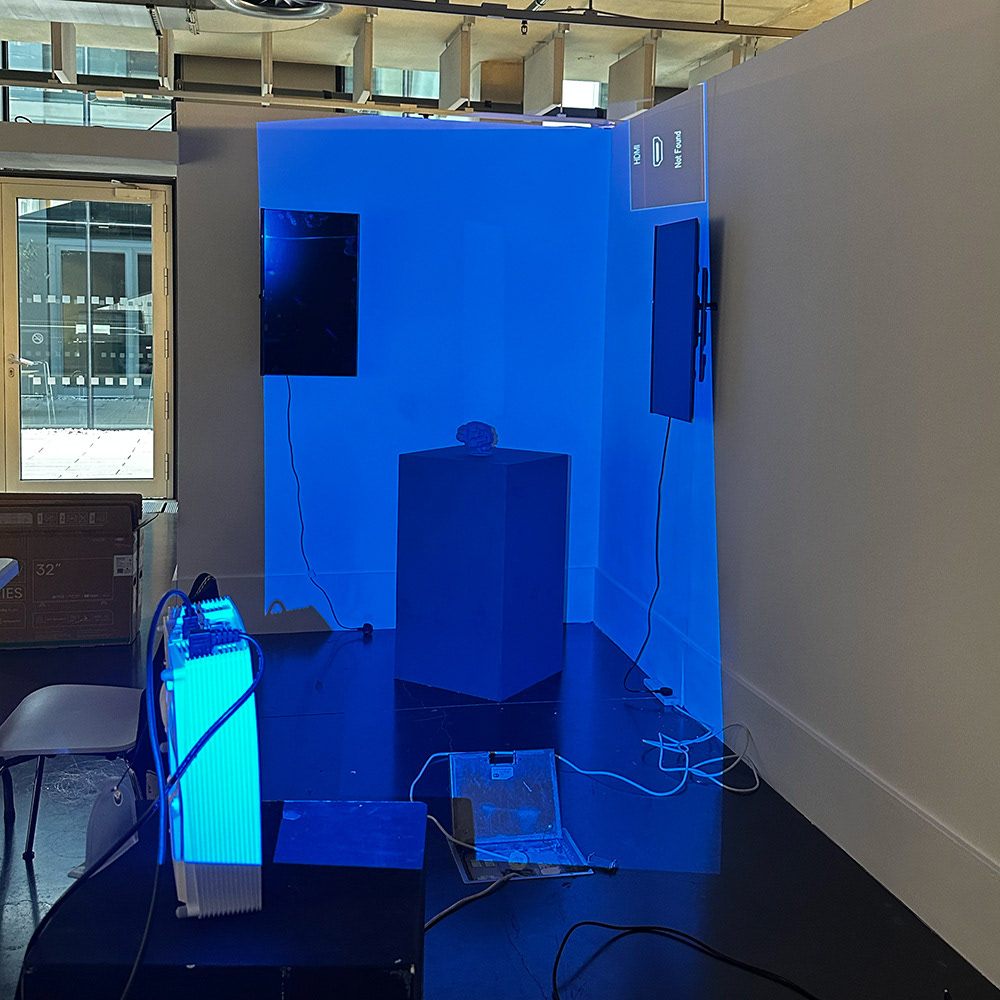

Summer Crit 03

By the third summer crit, the project had become more cohesive, combining the glowing brain with live media and sound-based interaction. The brain was placed under a UV light strip on a timer, pulsing like digital notifications, while a vertical screen played live TikTok videos. Using MadMapper and Synesthesia, I projected glowing green dots and pulses directly onto the brain, which reacted to both the videos and the sounds made by the audience. This created a more dynamic installation where the brain felt alive, constantly lit up by external forces. The piece developed into a stronger metaphor for how our thoughts and emotions are shaped, triggered, and even controlled by the endless flow of media and the people around us.

The summer crit helped me see how all the elements, light, projection, video, and sound, could finally work together in a gallery setting. What had started as a fragile experiment now felt like an integrated environment where the audience became part of the system, influencing the glow of the brain just by being present. It also made me realise the importance of designing the work with the exhibition space in mind: not just testing materials, but thinking about how people would encounter it, move around it, and experience its constant flicker between presence and absence. This crit marked the point where the project stopped being a series of disconnected trials and started becoming a unified installation.

Results and Reflection

The feedback from Summer Crit 3 pushed me to think bigger and more ambitious with the installation. The suggestion to use a 3D-printed brain rather than a model gave the piece a stronger sculptural presence, making it feel less like a prop and more like a central artwork. I was also encouraged to increase the sense of overstimulation by projecting TikTok content on two sides, surrounding the glowing brain with chaotic, fast-moving videos and layered sound. This shift highlighted that the work should not only show influence and control but also immerse the viewer in the overwhelming pace of digital culture. A reference to Nam June Paik’s pioneering use of video and media overload gave me a useful historical framework, showing how my project connects to a longer lineage of art that critiques technology through saturation and sensory chaos. This reflection helped me see that the final piece should lean into excess and fragmentation, making the brain a node caught in the noise of contemporary media.

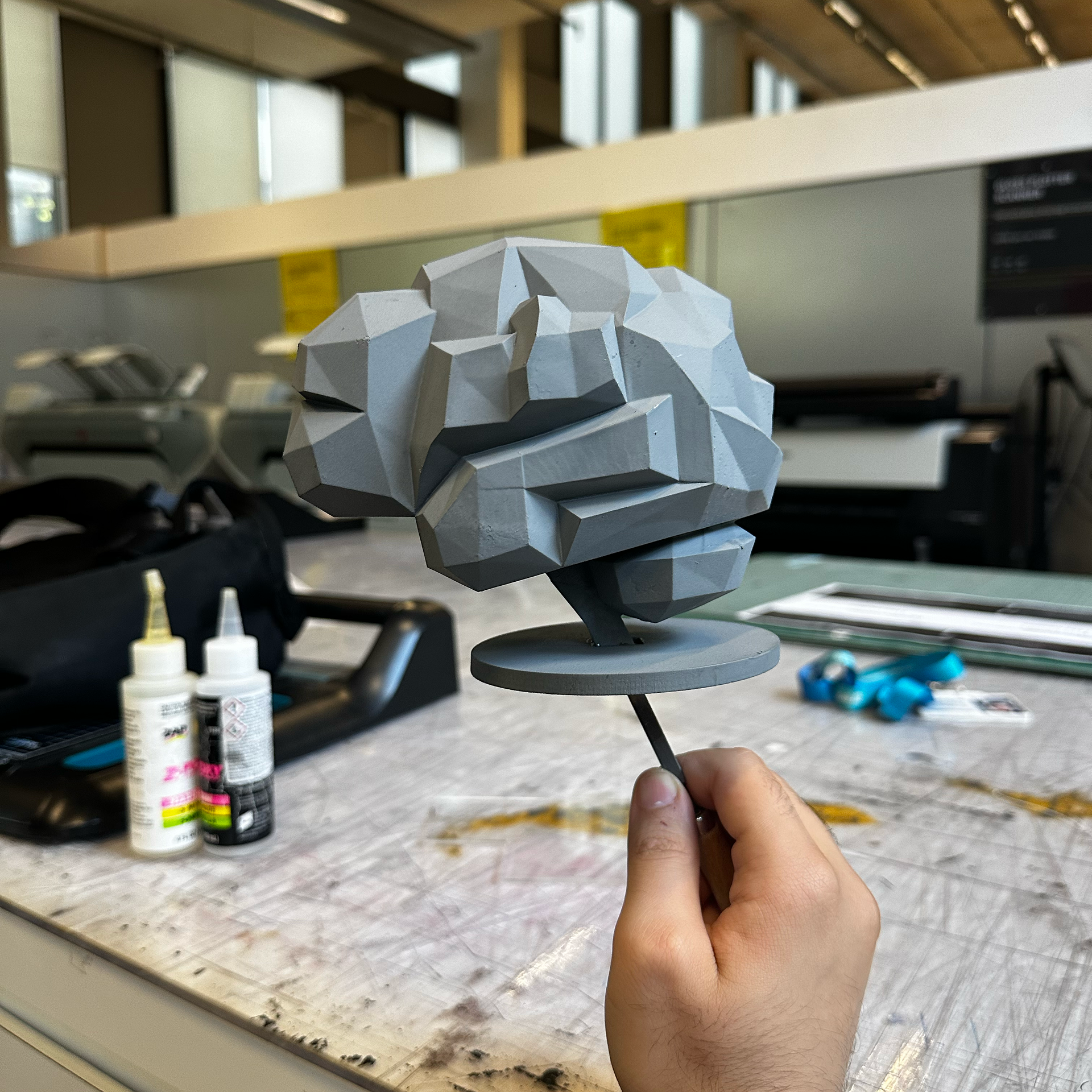

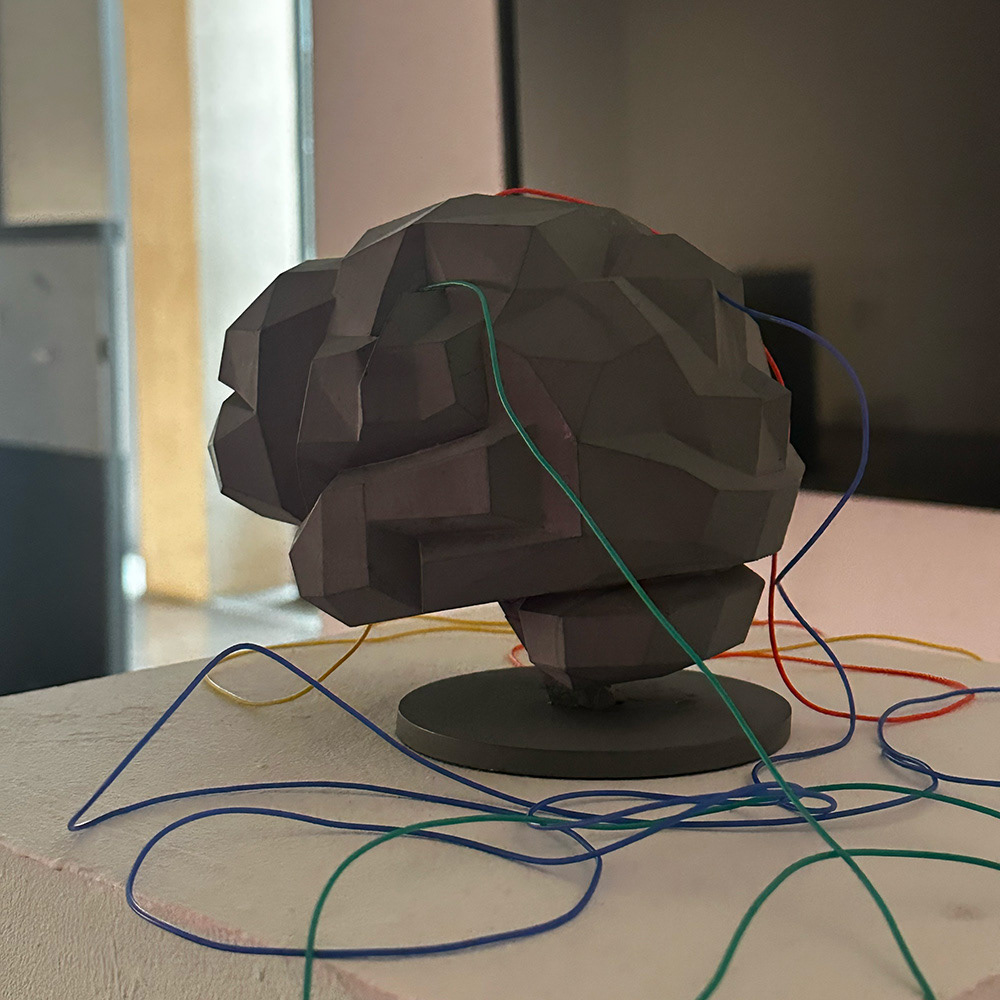

3D Printed Geometric Brain

As the project developed, I decided to move from using a ready-made brain model to creating a 3D-printed version. This step gave the piece a stronger sense of authorship and precision, allowing me to design the brain specifically for projection rather than adapting an existing object. Building the 3D model also helped me understand the structure in more detail, breaking it down into layers and curves that could catch and distort light in interesting ways. Having the brain printed made it feel more like a finished sculptural object at the centre of the installation, rather than a placeholder, and it opened new possibilities for integrating projection mapping with accuracy. The process of modelling and printing became part of the artwork itself, showing how digital tools and physical making could combine to create a form ready to carry both light and meaning.

Major Research

As the project reached its final stage, my research shifted towards consumerism and how it shapes our minds in ways that feel increasingly dystopian. Viral products like Dubai chocolates and trending gadgets such as Labubus show how easily attention is steered by platforms that turn desire into habit. This reflects what Guy Debord (1994) describes in The Society of the Spectacle, where images and commodities dominate our lives, directing how we think and act. Similarly, Jean Baudrillard (1998) argues that consumption is no longer about need but about signs and symbols, where buying becomes a way of performing identity. Neuroscientific studies echo this, showing that advertising and overstimulation trigger reward pathways in the brain, nudging us toward impulsive choices (Knutson et al., 2007). These perspectives helped me frame the glowing brain as a symbol of how consumer culture hijacks thought itself, reducing individuality to patterns of following, buying, and obeying.

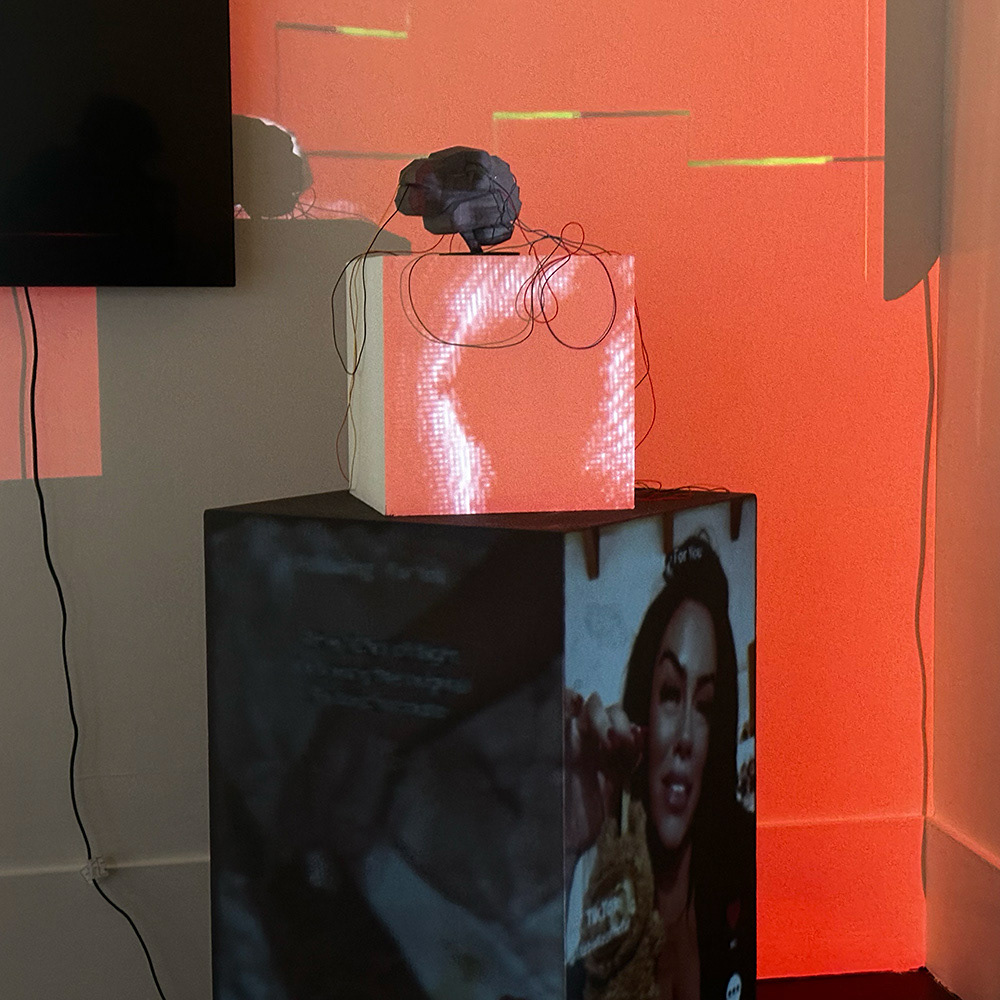

Re:Charge Final Installation

The final installation brought all the elements of Re:Charge together as a complete work. At the centre was the 3D-printed brain, wrapped with coloured wires to emphasise its connection to networks and systems of control. Around it, two large screens played looping TikToks, while two more were projected onto the pillar beneath the brain, surrounding it with a constant flow of viral content. The sound from these videos blended together in a chaotic stream and directly interacted with the brain, which responded through glowing pulses, flickers, and signals mapped onto its surface. This gave the impression that the brain was functioning through the same logic as social media, reacting to likes, trends, and noise. The choice of green and red as the dominant colours created a charged atmosphere: red suggesting overstimulation, green suggesting energy, Together, these elements staged a dystopian vision of how consumer media and digital culture continuously stimulate and shape our thoughts.

Artist Statement

My work tells the story of how digital culture and consumerism seep into our minds, shaping the way we think in ways that often feel unsettling. Re:Charge places a 3D-printed brain, wrapped in coloured wires, at the centre of a storm of TikTok videos, projections, and sound. Light and moving images ripple across the surface of the brain, pulsing in red and green as it responds to the noise surrounding it.

This setup reflects the world we live in now, a place where our thoughts are constantly tugged at by trends, ads, and endless viral content. The screens, the overlapping sounds, and the never-ending flow of videos mirror the overstimulation of consumer culture, where attention itself is turned into a commodity. Re:Charge suggests a dystopian present: one where our minds risk being caught in loops of likes, signals, and instructions, reacting automatically instead of choosing freely.

Reflection

Working on the final installation was the moment where everything I had been testing finally came together in a single work. Seeing the brain wired and reacting to the sound made the project feel alive in a way that earlier experiments could only hint at. The feedback reminded me that what gave the piece its strength was the way all the elements, the videos, sound, projection, and colour scheme, worked together to show how our thoughts are constantly influenced by consumer culture. This final stage also taught me the importance of scale, setup, and context. More than anything, the installation confirmed that the project was about how we live inside a system that keeps shaping us, often without us realising.

References

Academic & Theoretical Sources

Bachelard, G. (1994). The Poetics of Space. Beacon Press.

Baudrillard, J. (1998). The Consumer Society: Myths and Structures. Sage.

Cramer, F. (2015). ‘What is “Post-digital”?’, in Cox, G. & Przybylski, A.J. (eds.) Postdigital Aesthetics: Art, Computation and Design. Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 12–26.

Debord, G. (1994). The Society of the Spectacle. Zone Books.

Derrida, J. (1994). Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning and the New International.Routledge.

Dunne, A. & Raby, F. (2013). Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming. MIT Press.

Fisher, M. (2014). Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures. Zero Books.

Foucault, M. (1977). Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Vintage.

Ingold, T. (2013). Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture. Routledge.

Jameson, F. (2005). Archaeologies of the Future: The Desire Called Utopia and Other Science Fictions. Verso.

Knutson, B., Rick, S., Wimmer, G.E., Prelec, D. & Loewenstein, G. (2007). ‘Neural predictors of purchases’, Neuron, 53(1), pp. 147–156.

Phelan, P. (1993). Unmarked: The Politics of Performance. Routledge.

Salter, C. (2010). Entangled: Technology and the Transformation of Performance. MIT Press.

Zuboff, S. (2019). The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. Profile Books.

Literary & Poetic References

Marvell, A. (1681). The Garden.

Maughan, T. (2019). Infinite Detail. MCD Books.

Yeats, W.B. (1920). The Second Coming.

Art & Media References

Lozano-Hemmer, R. (2006). Pulse Room. [Interactive installation].

Paik, N.J. (Various works, incl. TV Buddha and media-saturated video walls).

Tee Ken Ng. (2023). UV laser vinyl animations. [Instagram].

Wurtz, D. (2022). UV Laser Drawing on Glow Vinyl. [YouTube video].

Villareal, L. (2015). Infinite Composition. [Public light installation].

Munro, B. (2015). Field of Light. [Light installation].

Centre for International Light Art (CILA). (Ongoing). Unna, Germany.

LaserAnimation Sollinger. (2025). Laser Mapping & Illumination Projects.

Cultural & Popular Media References

Metropolis (1927). Directed by Fritz Lang.

Blade Runner (1982). Directed by Ridley Scott.

The Archivists (2020). Directed by Igor Drljaca.

The Walking Dead (AMC, 2010–). Selected episodes.

Star Wars franchise (1977–present). Various depictions of lasers, lightsabers, and blasters.

Other Sources (Articles, Blogs, Reviews)

Coverley, M. (2020). Hauntology: Ghosts of Futures Past. Folk Horror Revival [Book Review].

Fort, P. (2024). ‘Why vinyl is booming again despite the digital age’, Financial Times.

Sample, I. (2024). ‘Nuclear fusion breakthroughs boost hopes for clean energy and space propulsion’, The Guardian.

Skains, R.L. (2021). ‘An audio professional’s take on vinyl’, Aesthetics for Birds.

Wilkinson, R. (2019). Infinite Detail by Tim Maughan. Strange Horizons.